The Husbandman's Assistant;

SKIRVING William (1792)

£2500.00 [First Edition]

RADICAL HUSBANDRY: UNFINISHED AS THE AUTHOR WAS TRANSPORTED TO AUSTRALIA

The Employments and Instructions to which a judicious and practical Farmer would urge the Attention of a Son, whom he wishes to make a complete Husbandman; and the objects of Attention in entering upon Leases of Ground, and in managing them to the best Advantage.

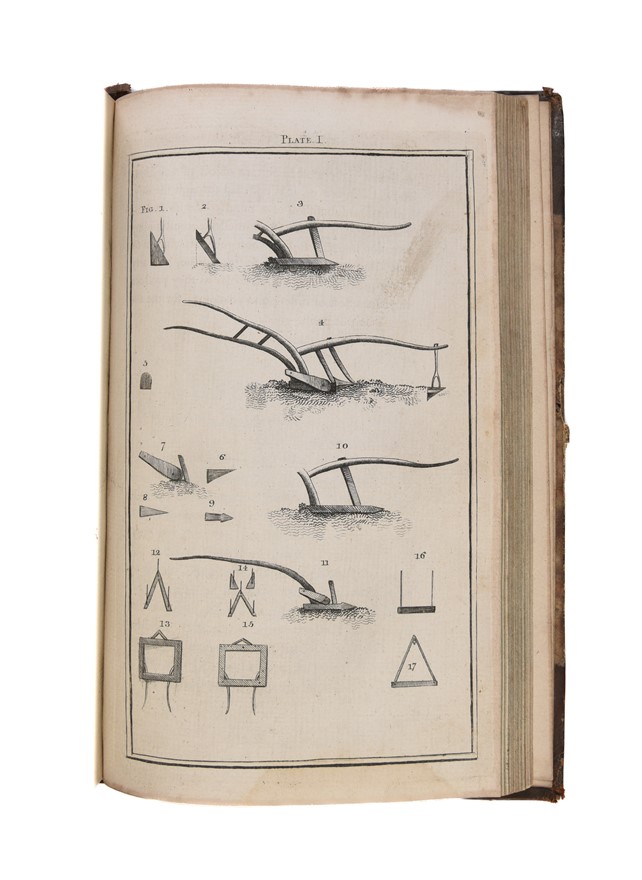

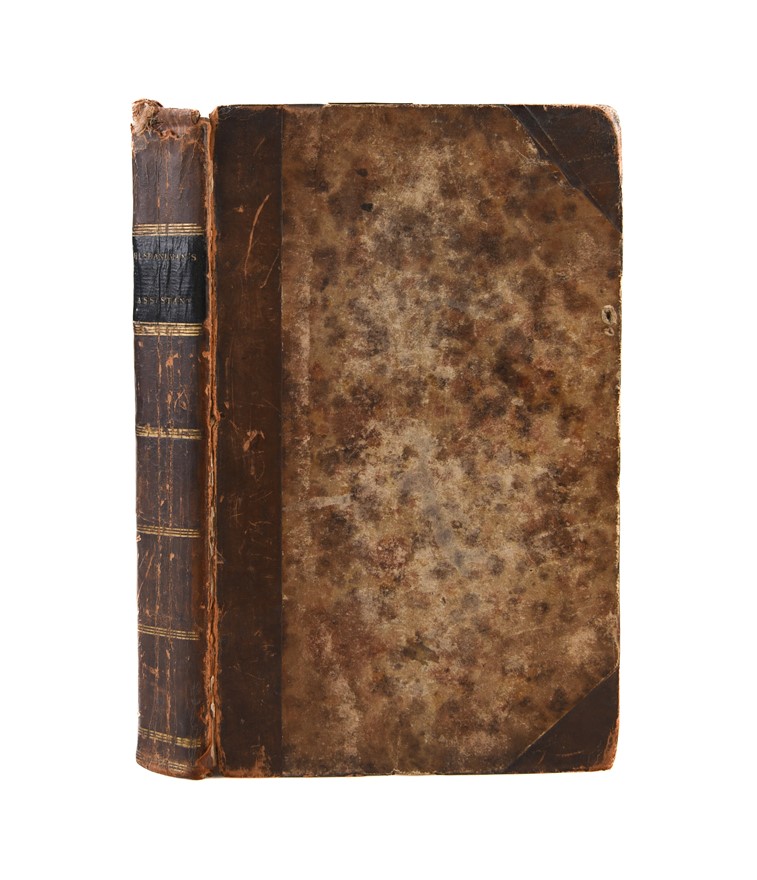

First Edition. 8vo (207 x 130mm). xxvii, 29-446pp., with an engraved plate of a plough. Title-page lightly browned and dusty, some spotting in places, a few chips and closed tears to the edges of a few leaves (not touching the text). Early 19th-century calf-backed marbled boards, spine ruled in gilt, black leather and gilt label, plain endpapers (upper headcap torn and ragged, joints split but holding firm, rubbed and bumped at the corners and edges).

Edinburgh: by Hugh Inglis, for the Author,

Very Rare. Edinburgh University and National Library of Scotland only in the UK; University of Kansas and Toronto only in the USA. OCLC adds a copy at the BL and University of Reading and New York Public Library. A second volume is mentioned throughout the book (and was clearly written) but it was never published as the author was transported to Australia in 1794

A wide-ranging practical husbandry manual specifically addressed to younger farm labourers ("this most useful class of men") who were not from the land-owning classes and with a view to revolutionising Scottish agricultural practices. The author became embroiled in the widespread fears of uprising in the United Kingdom after the Revolution in France and the publication of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man and was found guilty of distributing a radical pamphlet and transported to Australia where he died of dysentery in 1796.

This book shows the strong influence of Skirving's father, also William, and argues that it is essential for young people to learn practical agricultural skills, "to guide and determine the tender shoot of reason in the opening breast" (ix). Skirving's book is particularly targeted at the sons of poorer farmers rather than, "young farmers, who,se parents are opulent" (xi). Skirving had studied at the University of Edinburgh before leasing a farm at Damhead in Haddingtonshire, this failed but he later inherited his father-in-law's property including a farm at Strathruddie.

Skirving notes:

"I have observed, that labouring people read little or none: that nevertheless they were very intelligent in such matters as were taught them in youth...for whatever the mind receives in youth, it embraces with affection...and hence also I concluded, that agriculture could only be forwarded towards perfection, by interesting the affections of those who are engaged in its labours; and that it was therefore of the greatest importance, to engage the heart, while young and tender, to those principles of science, the application of which, in practice, would open their minds to the reason of things" (xvii)

The main body of the manual contains instructions on herding and driving cattle, managing the plough and sewing and reaping.

We begin though, at the end of the volume, to see the emergence of Stirving's revolutionary feelings when he turns to the management of farm workers: in a long footnote on the "Duties of Upper Servants [i.e. farm managers], he writes:

"The moral evil system has not failed to take advantage of the benefit of representation. Hence it is, that we find the patterns of the leading principles in those governments kept up...The principle of despotic government is fear; and accordingly, as Montesquieu has demonstrated, the perfection of such governments depends upon the greater terror with which the magistrate clothes himself. Here they take care to keep the instruments of torture and death always in view, and in continual operation...We, in Britain, are especially to blame...while our constitution admits to a distinguished and enviable place in he commonwealth the patterns of virtue and goodness, we suffer these sacred feats to be profaned with the most corrupt and the vilest examples"

The final pages of the Appendix also begin to draw close to the fears surrounding public meetings that dominated the prosecutions around this time:

There is much wisdom in the plan of association of the farmers in Mid-Lothian...Brethren, we are justly esteemed the most stead, and the most moderate class of inhabitants in every kingdom. Let us, conscious of our patient, submissive, and moderate general disposition, step forth, and be prepared to aid the wise and the good....If, there, there are but three in a parish attentive to the good of mankind, let them form themselves into a permanent society; let them join with, was it but two parishes, and send up a noble triumvirate to the country town...."

Skirving's entry in the ODNB states that:

"The final stages of work on this publication [The Husbandman's Assistant] had brought the Skirvings to Edinburgh amid mounting enthusiasm for political reform inspired by the French Revolution". It is clear though from a closer reading of the text that Skirving was already beginning to hold emerging radical views that would only have been strengthened when he reached Edinburgh.

"It was not long before Skirving suffered for his political activities in the alarmist conservative climate of Edinburgh during the French Revolution. He was first arrested in August 1793 for distributing copies of a radical pamphlet written by George Mealmaker of Dundee and printed by Thomas Fysshe Palmer, who was transported for his action...Skirving was tried before the high court in Edinburgh on 6 and 7 January 1794, and bravely or unwisely insisted on conducting his own defence. He was sentenced to fourteen years' transportation. After a short period of imprisonment in the Edinburgh tollbooth he was transferred to Newgate, London. The transport, the Surprise, left St Helen's on 1 May 1794, carrying Skirving, Palmer, Margarot, and Thomas Muir, and it arrived at Port Jackson, New South Wales, on 25 October. Skirving bought a small farm shortly after his arrival and named it New Strathruddie in memory of his wife. He died from dysentery in Port Jackson on 19 March 1796 and was buried on the same day at St Philip's Church, Sydney" (ODNB).

Provenance: Robert Kirk, contemporary signature in the upper blank margin of the title-page.

Stock Code: 250256